MSA Turns 60

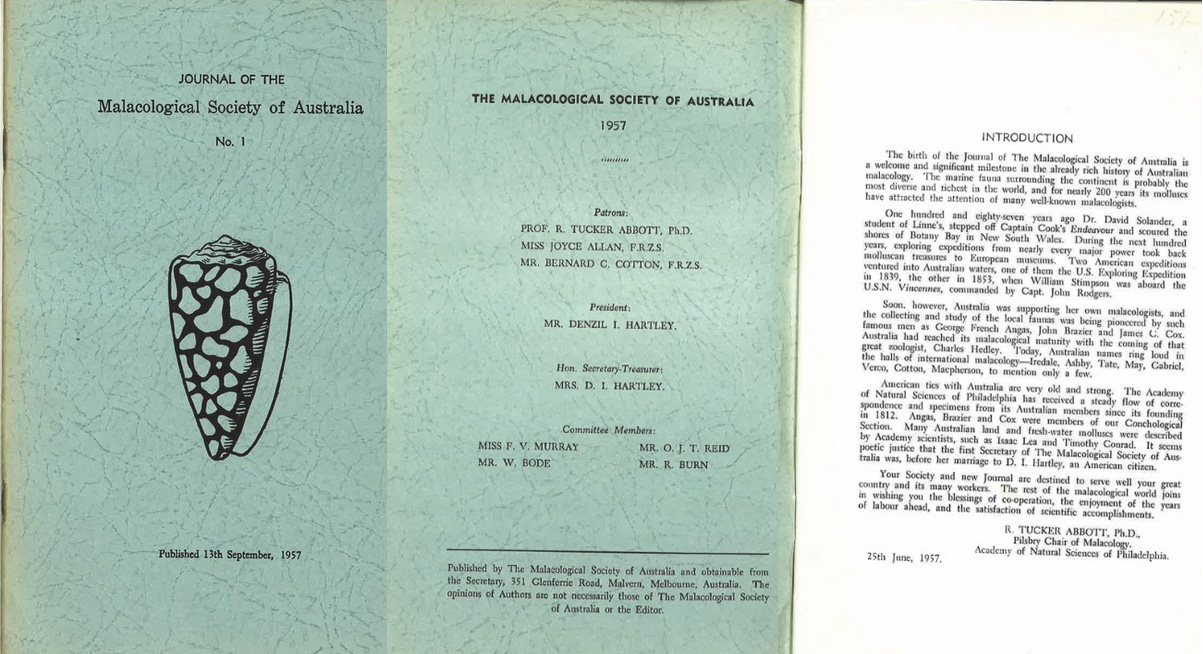

December 2016 marks 60 years since the first meeting of the Malacological Society of Australasia. In honour of our birthday, we’ll be posting a new fact each week to showcase discoveries, events, and people that have shaped malacology over the years.

We’re asking all members to dig into their archives and memory banks and send ideas and photos to MSAturns60@malsocaus.org.

To see the fun facts each week, like us on Facebook or follow @MalSocAus on Twitter. Postings will also be made here periodically.

Week 60: FIRST MSA CONFERENCE IN NEW ZEALAND

In 2018 the triennial meeting of the Malacological Society of Australasia will be held, for the first time, outside of Australia. Between the 2nd and 5th December, delegates from the Australasian region and beyond will convene at the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa in Wellington. The conference programme will include presentations on the latest scientific advances in molluscan research, ranging from shellfish aquaculture to systematics and taxonomy of select groups. Southern endemism will be one focus of the conference. Social events will include a mixer on the evening of December 2nd to welcome conference attendees, and a conference dinner where we will celebrate the 60th anniversary of the MSA. Over the next few weeks we will release more information on the MSA website. A working list of symposia will be released soon, along with a request for any additional ideas from the community. Following that a call for abstracts for oral presentations and posters will be made and the conference registration site will go live. Students are encouraged to look out for travel grant applications that will be available later in the year. For those of us who have moved beyond our student days, keep in mind that there will be a reduced conference fee for MSA members. This will all be detailed on the MSA website, so please watch that space. If you need any further encouragement to attend Molluscs 2018, come and meet the only Colossal squid (Te Wheke Nui) on display in the world! As Vice-President of the MSA and lead organizer of the local committee in NZ, I look forward to welcoming you to Wellington NZ in December! ~ Simon Hills

Week 59: MSA CELEBRATES DARWIN DAY 2018

Today is International Darwin Day! Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution as descent with modification was clearly revolutionary for his time. These views were in no small way influenced by his observations as a naturalist, geologist and biologist during his 5 year voyage on the Beagle, on which he visited South America, South Africa, New Zealand, and Australia, and several islands in between.

Of course, molluscs could not escape Darwin’s attention during his travels. In fact, he spent a great deal of effort trying to understand the paradox of the wide distribution of particular land and freshwater snail species, especially on remote islands, which was discordant with their low dispersal capabilities. In letters to family and colleagues he wrote:

‘No subject gives me so much trouble & doubt & difficulty, as means of dispersal of the same species of terrestrial productions on to oceanic islands. –Land Mollusca drive me mad, & I cannot anyhow get their eggs to experimentise on their power of floating & resistance to injurious action of salt-water.’ (His substantial skill set did not appear to extend to snail husbandry).

And further:

He had obviously satisfied himself on this point by the time he wrote Origin; where he states:

‘It occurred to me that land-shells, when hibernating and having a membranous diaphragm over the mouth of the shell, might be floated in chinks of drifted timber across moderately wide arms of the sea. And I found that several species in this state withstand uninjured an immersion in sea-water…’

Darwin never ceased searching for evidence of the transportation of both freshwater and terrestrial molluscs. It is perhaps fitting that his penultimate publication was ‘On the dispersal of freshwater bivalves’ (Nature 1882, Vol 25:649, p529) where he describes several examples of bivalves attached to various other animals, including beetles, frogs and newts. ~ Carmel McDougall

Week 58: MALACOLOGY: A STUDENT’S PERSPECTIVE

My name is Josh Mason and I am an environmental student at Curtin University in Western Australia. I am currently undertaking my honours in collaboration with the Western Australian Museum (WAM). My project is looking at the morphological and genetic diversity of Angaria (a genus of marine intertidal gastropod) found along the WA coast. I’m also on the committee for the Curtin Environment & Agriculture Club (CEAC) and am a regular volunteer at WAM. But first, how did I get involved in malacology?

As an environmental student, you learn about all about the diversity of the natural world. But despite this, the groups of animals students get attached to or gain an interest in are those you hear most about, those most in the public eye, those that are always the big attractions at zoos and the like such as mammals, reptiles and fish. My first real introduction to molluscs was as many people may have been, through shells. For some background, a large shell collection donated to the university was divided up for identification by student groups. Everyone is familiar with shells, but the vast diversity of morphology that could be present in that room at one time was astounding, almost otherworldly, as it’s not like the common beach shells you see give any indication of the diversity that exists. Suffice to say I enjoyed that short time doing shell taxonomy, and when I heard of an opportunity to volunteer at WAM I took it. That began in early 2015 and I have enjoyed the time I’ve spent there over the last nearly 3yrs. The time I spent there working on molluscs was what led me to my current honours project, as an extension of a small investigative project I did into distributions of WA Angaria species during that time. I’d never known what group of organisms I wanted to study; in terms of study, animals have lots of complications and plants I’d never been much of a fan of their biology or taxonomy. So molluscs filled a niche for me, as they are still interesting with a broad diversity and distribution, but also for the most part sessile which makes for easier study as I’m sure some can attest to.

It wasn’t until recently on a snorkelling trip for my honours project to Rottnest Island that it really clicked though. I’m not someone that spends a lot of time in the water, or has been out to reefs. So it came as a shock when I found just how close to home some of the diversity I’ve been studying in labs and classes really was, and just a few meters from crowds of holiday-goers. You always hear about the breadth of life in the ocean that is just below the surface, but never had those words been truer to me than then!

I think I’m hooked now. And I’m learning that there is a small but highly dedicated community of molluscan researchers/collectors/enthusiasts. There is a huge potential for people to get invested in molluscs, but it doesn’t feel like there is a young community around it, and like many things has just been quietly aging away. I feel that we can contribute to the growth of malacology by increasing awareness, use of public events, and encouraging citizen science. The breadth of molluscs is well known to us, but to many, molluscs might be a bit of an unknown term despite passing familiarity with what many of the organisms that fall under its umbrella are such as clams, seashells, octopi, garden snails and slugs. In general, an increase in general awareness of what molluscs are, where they are found, and their diversity are needed. Staging public events to engage communities, aimed at all ages and levels of experience, can be organized to garner interest. For example, a beach walk, snorkel, or dive (which each can be aimed at broad or varying levels of experience) can be held by professionals, perhaps linked to local Naturalist clubs, at hotspots, much like tours through Kings Park or various protected reserves. Engagement can also lead to further projects and involvement like citizen science, where once an interest has been established, an individual or group can contribute to the knowledge of malacology through their own trips using tools such as Atlas of Living Australia’s BioCollect (https://www.ala.org.au/biocollect/) or through large annual events similar to BirdLife Western Australia’s Great Cocky Count (https://www.facebook.com/events/148590292412843/). As with everything relevant and targeted marketing is imperative. ~ Josh Mason

Week 57: FAREWELL HOPE MACPHERSON 1919-2018

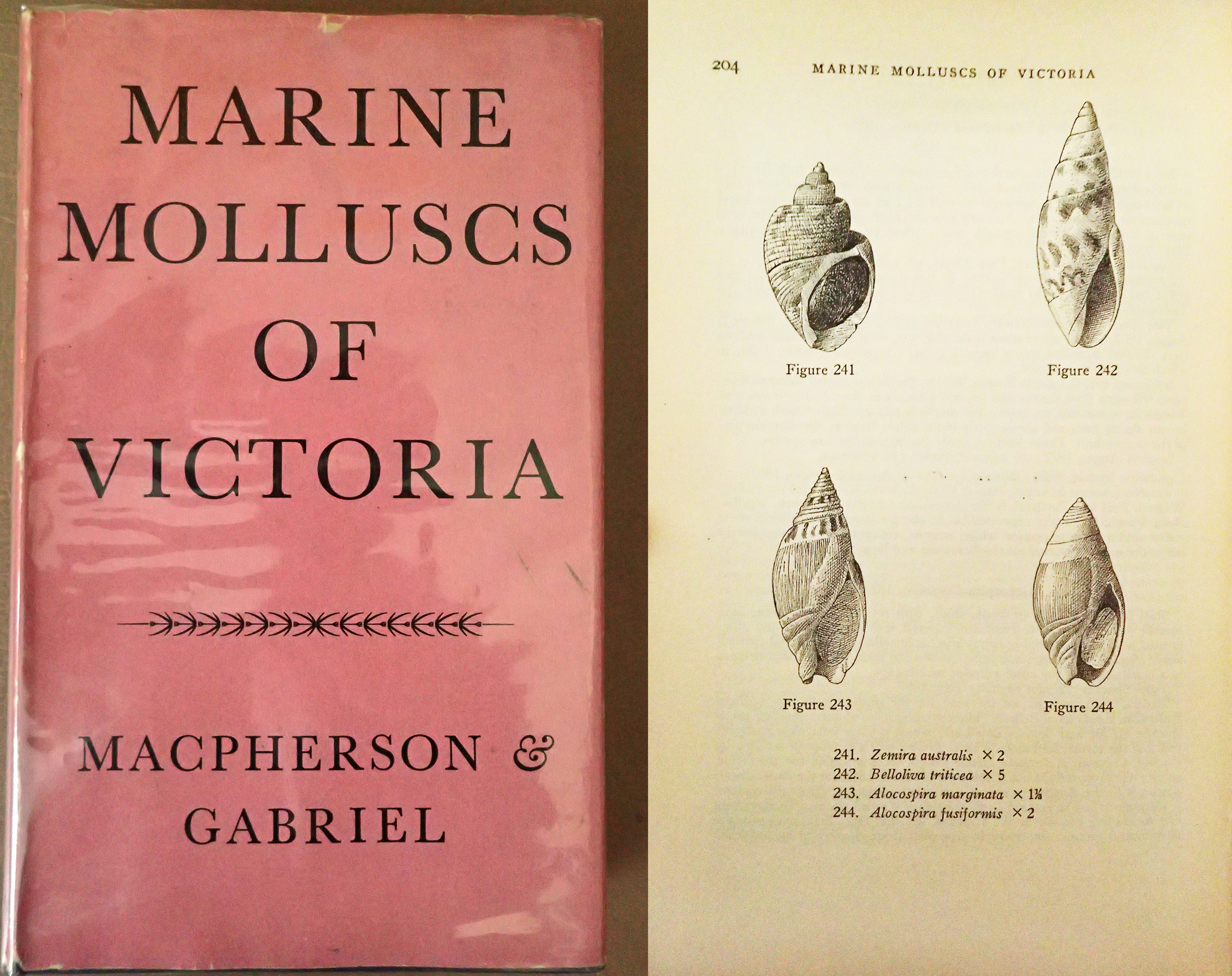

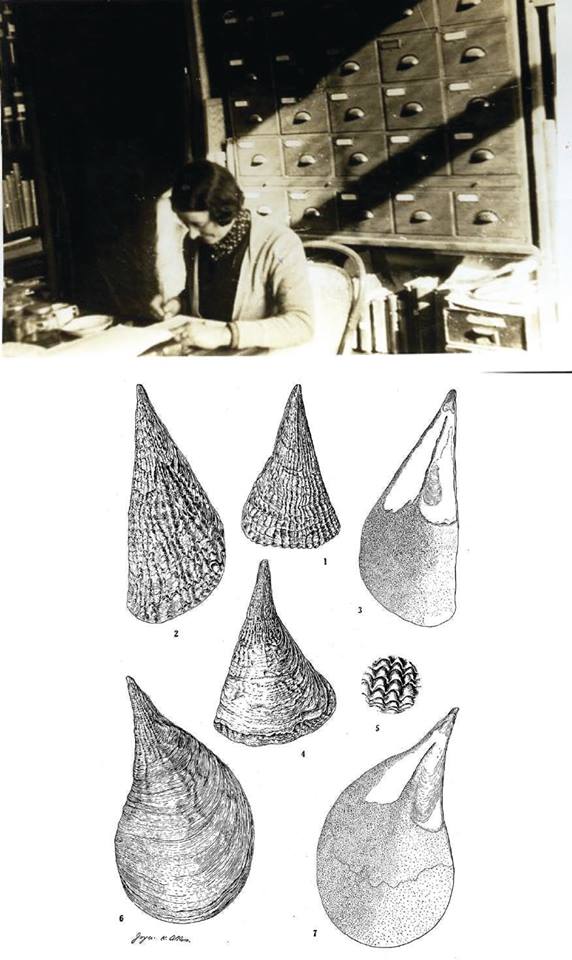

As we approach our target sixty posts for the MSAturns60 initiative, it is with sadness that we farewell the last of the founding members of the MSA, the late J. (Jessica) Hope Black (nee Macpherson) who passed away in Melbourne, Victoria on Thursday 25 January 2018, just short of her hundredth birthday. Hers was an extraordinary life which broke new ground in forging the active participation of women in a scientific career. After graduating in Science at The University of Melbourne, she was appointed Curator of Conchology at the National Museum of Victoria from 1946 until 1965 (when she had to relinquish her position after marrying, in accordance with the public service laws of the time – Carland, 2011). Her appointment and the scientific rigour that it brought to the collections was instrumental in encouraging the late Charles Gabriel to donate his important collection to the museum, thus securing key Victorian molluscan types, valuable documents and literature for posterity (Burn, personal communication).

Having published several papers amongst which she also described a number of mollusca, Hope also revised W.L. May’s “Illustrated index of Tasmanian Shells” in 1958 (see Week 52) and, with Gabriel, published the outstanding “Marine Molluscs of Victoria” in 1962 (see Week 13). She took part in several scientific surveys, including the Port Phillip Bay surveys from 1957 to 1963 and an Australian National Antarctic Research Expedition to Macquarie Island in 1959, where she was one of four participating women (Carland, 2011). Her enthusiasm made her a great advocate for amateur science, and the museum became a welcoming place of collaboration and great benefit to all involved. This tradition was continued by her successor, the late Dr. Brian Smith, and remains strong to this day.

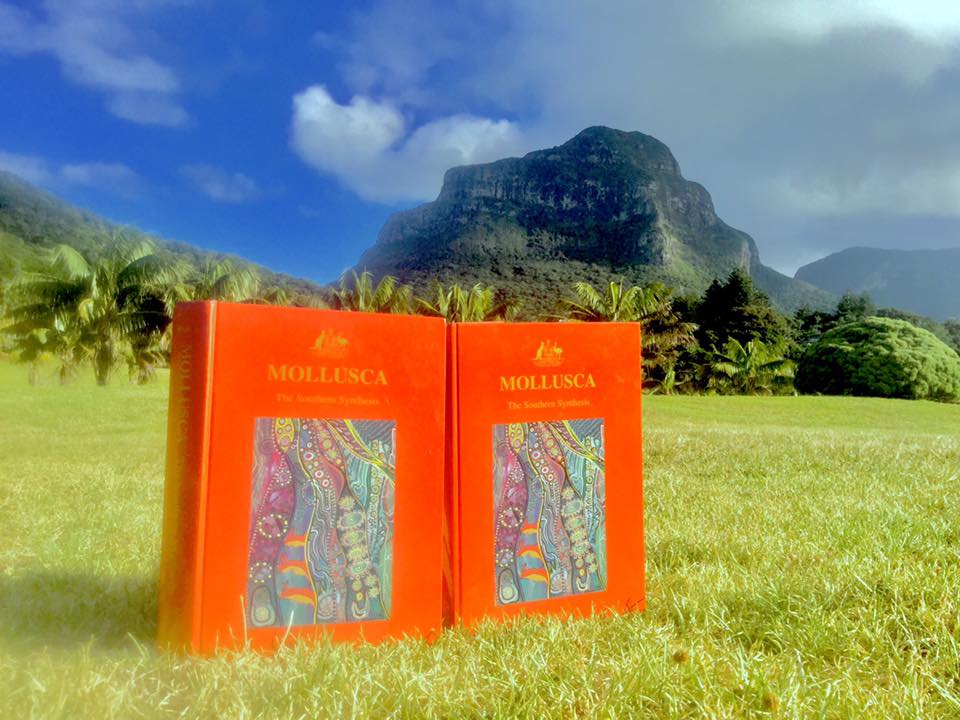

Hope’s later working years were spent as a science teacher in Victorian rural secondary schools (Carland, 2011). She had also undertaken a personal project to compile a brief biography of each contributor to Australian malacology, entitled, “Encyclopaedia of Malacologists” (Burn, personal communication). This work was never completed to publication stage, but a manuscript exists (Burn, personal communication) and it is insightful to see what she mentions of herself and which of her achievements she particularly highlights. Under the name “Black” she has a note stating “see Macpherson, Jessica Hope.” Under “Macpherson, Jessica Hope (Mrs. Ian Black)” she provides the following information: “1919. Born Hamilton, Victoria. Curator of Molluscs, Museum of Victoria 1946-1965. Foundation member, Malacological Society of Victoria* and of Marine Study Group. President, Malacological Society of Australia, 1973. Author of a number of papers and ‘Marine Molluscs of Victoria’. Editor of Port Phillip Survey 1957-1963, No. 27, 1966; No. 32, 1971” (Burn, personal communication). This entry is likely to have been completed some 10 to 15 years ago and hints that in her scientific work, Hope preferred to be known by her maiden name (Burn, personal communication). (However exceptions to this are her contribution to a chapter on molluscan egg masses in “Marine Invertebrates of Southern Australia, Volume 2”, 1989, and also her account entitled ‘History of discovery’ in “The Southern Synthesis”, 1998, where she used her married name).

(* – more correctly, this should have read “Malacological Club of Victoria” – see Vafiadis in Newsletter of the MSA, no. 159, 2016).

Hope was honoured by being inducted into the Victorian Women’s Honour Roll at a ceremony in Parliament House on 6th March, 2012 (Carland, in Cram 2012). Phyllodesmium macphersonae (Burn, 1962) (see photograph from Week 1) also seems to be the only (although this needs to be verified) molluscan species that is named in her honour (Burn, personal communication).

Even into her late 80s and early 90s, Hope often attended the annual Christmas lunch of the Marine Invertebrate Lab at Museum Victoria, her quiet presence inspiring all. I also had the good personal fortune to have received a letter from her in 2009 after sending her some sea slug images.

As this series of 60 posts to celebrate the MSA now nears its completion, having begun with Hope as its foundation in marking the MSA’s 60th anniversary, it is fitting that she is now also present towards its conclusion. Let us carry on her productive legacy!

Many thanks to Robert Burn and Don and Val Cram for valuable information and discussion, and to Don Cram for the photograph of Hope Macpherson. ~ Platon Vafiadis

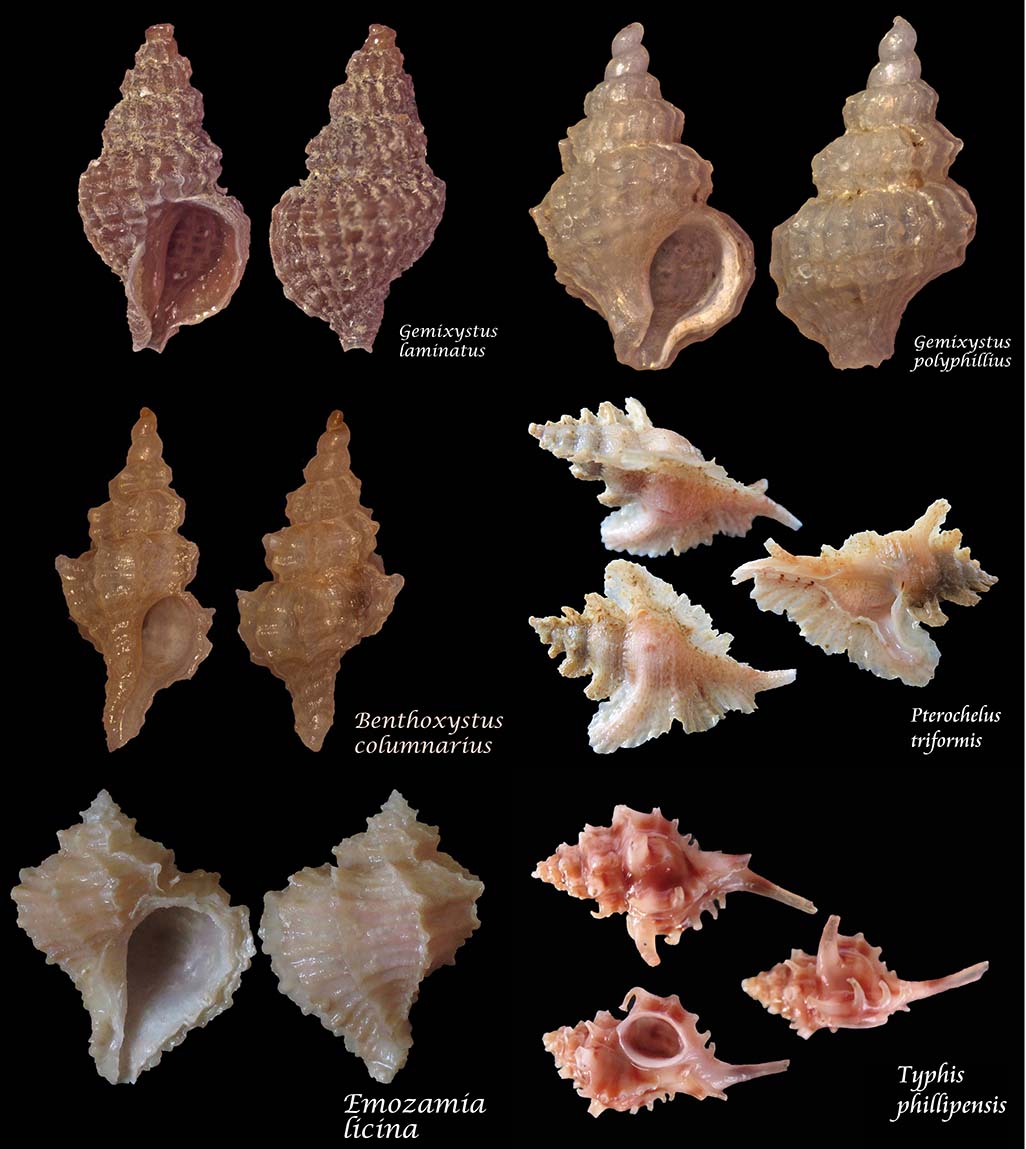

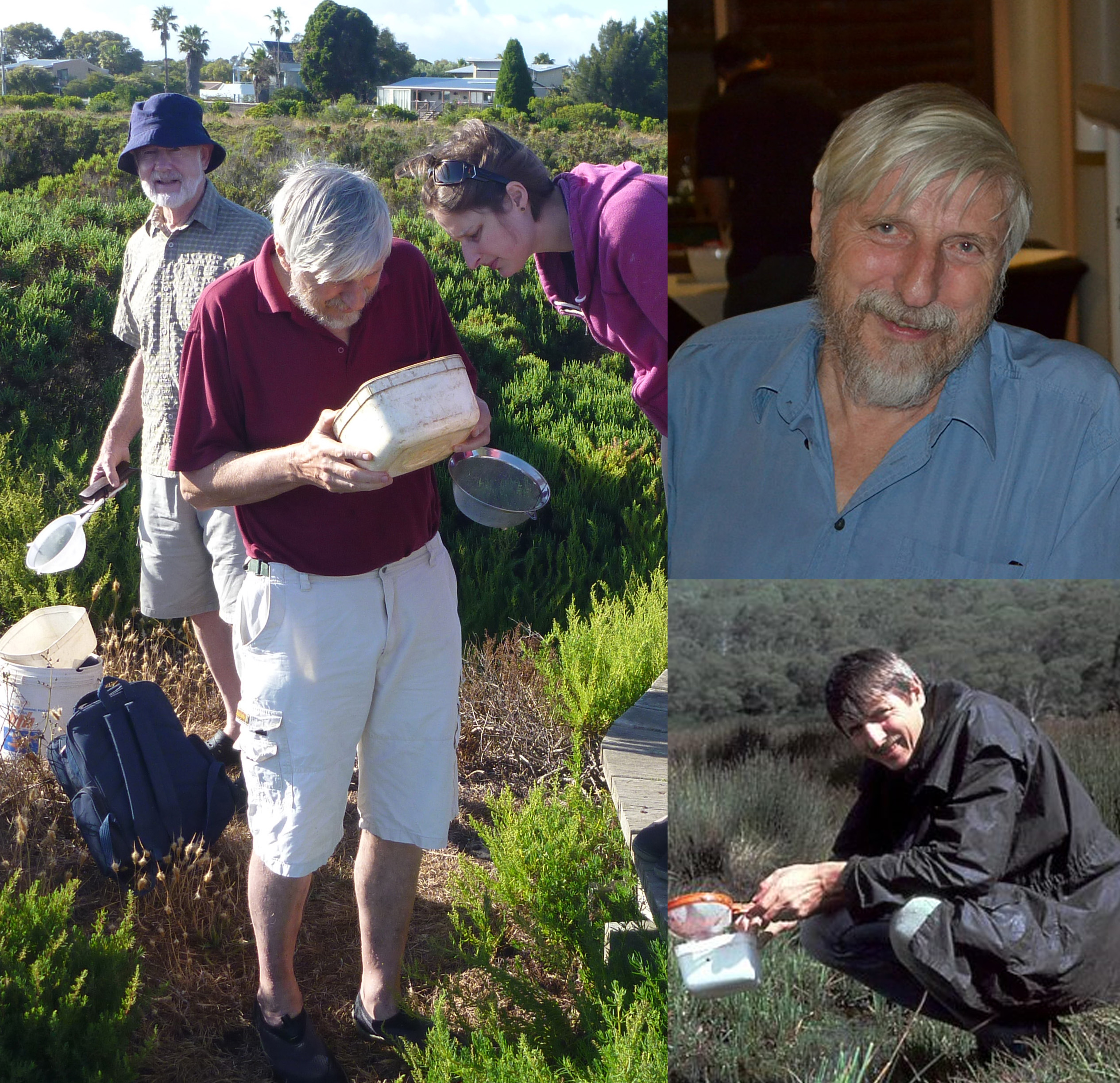

Week 56: HORTON HEARS A WHO

Horton hears a Who is a story written by Dr. Suess about an elephant, Horton, who discovers a microscopic community on a flower puff as a result of his exemplary hearing. He then spends a lot of time trying to convince others (who cannot hear quite as well) that this microscopic world is real, while some try to prove him mad. Sound familiar? Anyone? ‘Micromolluscs’ is a catch-all term for molluscs that are at adult size no more than approximately 1 cm. While some molluscan families are entirely micro, others are not.

Studying this fraction in the marine realm is challenging for a number of reasons and yet so many cannot resist! Firstly, collecting micros is difficult as you need to use special techniques. You cannot simply pick up a micro on the reef flat as you would a triton or giant clam. You usually need to collect substrate first and then scrub, swirl or patiently wait for the little gems to crawl off.

Studying micros is also complicated. You cannot simply study the details of shell characters with the naked eye or a loop, but instead you need a very good microscope and generally an SEM as well. Often the specimen that you have carefully cajoled into place for photography goes zinging off the petri dish, or just as bad, is crushed by a not so gentle touch. In many cases, the best way to observe characters is from a photo you have taken of the subject!

If you are interested in incorporating a molecular component into your study of micromolluscs, well there is no respite there. Although new advances have been made, it can be very hard to obtain enough genetic material to sequence genes from a single specimen.

So why bother? Complete masochism? Because this component of ecosystems broadly (beyond molluscs) offers opportunity for huge discovery – from new branches in the tree of life to new species, especially in little studied parts of the world. Beyond biodiversity and evolution, ecologically, micromolluscs offer insight into the base (or at least the nether regions) of our marine foodwebs. I think for me, a bonafide novice, it is when you expect nothing in a petri dish, to the moment you think you have found something special, to the confirmation in a stunning image that makes the journey worthwhile. Ok, I have to admit that there is something truly meditative in sorting for micros. It is a privilege to delve into the hidden beauty of tiny biodiversity, available in almost every habitat, often in abundance, if you simply take the time to look! ~ Peter Middelfart and Lisa Kirkendale

Week 55: MOLLUSCS, KIDS, AND EDUCATION

There’s no doubt that molluscs hold a particular fascination for kids – maybe it’s the striking variation of their shells, their alien appearance, or their elusive pervasiveness? It’s almost impossible to visit any Australian beach in summer and not see at least one child excitedly collecting seashells, scrambling over hot sand from one carbonate jewel to the next. This enthusiasm needs to be stoked from a young age so that they continue to develop their appreciation for the natural world as they become adults. Parents and teachers can do this in a variety of ways: Bushwalks can include scavenger hunts where children take photos of particular molluscs. Garden snails and slugs can be collected and observed after a rain shower (see photo of snail race below). Seashells can be glued onto a painting the child does of the live animal and its habitat. Stories can be written about molluscs seen in their favourite nature documentaries. For older kids, online resources, field guides, articles and books may also be appropriate. It’s amazing how often molluscs appear in various media articles – keep your eye out for these and share with any kids in your life. At worst, they’ll be disinterested. At best, you’ll foster the next generation of budding malacologists and environmentalists!

There are lots of good online resources about molluscs for teachers and parents (e.g. http://www.biokids.umich.edu/critters/Mollusca), but other than the valuable museum webpages catered for the general public, there are very few within Australia. One of the more notable exceptions is the mollusc module from the Marine Education Society of Australia, although this group has now been enfolded in the Australian Association for Environmental Education. The MSA Council has discussed developing educational materials related specifically to Australian molluscs, and we’d love to hear from anyone interested in leading or contributing to this initiative! ~ Rachel Przeslawski

Week 54: CELEBRATING WOMEN IN COLLECTIONS

Recently, someone shared a very interesting paper with me, and I’d like to share it with the Australasian malacological community now. It’s reading things like this that makes me appreciate the interconnectedness of history, science and art. It’s an article co-authored by longstanding MSA member John Healy, Curator of Molluscs at the Queensland Museum (QM). The article examines the life of Elizabeth Coxen (1825-1906), who seems to be the first woman curator, in this case at the QM, in any natural history museum in Australia. She was a conchologist, meteorologist and horticulturalist. In middle age, she became the first person paid to oversee any part of the QM collections. She was widely respected in the local scientific community, well connected to international scientific circles, and was the first woman to be elected as a member of a scientific organisation in Queensland (Royal Society of Queensland).

The QM runs a seminar series marking International Women’s Day, and this paper was written in response to a talk entitled ‘Founders of the Queensland Museum and the women who shared their vision’. One of the authors of this paper had also previously created an exhibition in 1997; ‘Brilliant Careers: Women Collectors and Illustrators in Queensland’, in which Elizabeth Coxen was just one of 34 women featured.

Elizabeth Coxen (nee Isaac) was born to wealth in England, and emigrated to Sydney with her family in 1839, at the age of 13. Her brothers headed north and in just a few years, Elizabeth was also living in Brisbane. By 21 years of age, she had met her future husband, Charles Coxen, likely through her brother, who was also interested in natural history, and had accompanied Leichhardt on some travels in the area. She and Charles married when she was 26. A few years later her parents returned to England, and in a few years her three brothers had all passed away. I’ll leave the rest of the story to the paper: McKay, J. & Healy, J.M. 2017. Elizabeth Coxen: pioneer naturalist and the Queensland Museum’s first woman curator. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum–Nature 60: 139-160.

Images sourced from this article with (L) Elizabeth Coxen and (R) Hand coloured plate of species described by Brazier based on specimens from the Coxens. ~ Nerida Wilson

Week 53: FRESHWATER AUSTRALIAN MUSSEL RESEARCH

McMichael & Hiscock published the most recent taxonomic overhaul on the Australasian freshwater mussels (Hyriidae) back in 1958. Their taxonomic framework for the group has been put to the test as new discoveries have begun to emerge within recent decades. In 1986, HA Jones et al. revealed spectacular morphological differentiation in several species of hyriid larvae (glochidia). Work from the late Keith F. Walker and others (e.g. CL Humphrey, F Sheldon et al.) outlined the problem of morphological plasticity in adult shells from varying habitats, making species identification often difficult. Never-the-less, shell characters are still important, as outlined by the most recent species description of Lortiella opertanea, published in the society’s own Molluscan Research by Ponder & Bayer 2004 which was based solely on shell morphometry. More recently, molecular analyses of Australasian hyriids has “rocked the taxonomic boat” with recent changes to New Zealand hyriid taxonomy (Marshall, Fenwick & Ritchie 2014) and raised some doubt with “cryptic speciation” revealed by Baker at al. 2004-2005 and Graf et al. 2015.

In 2010, I met Alexandra Zieritz in the World Conference on Malacology meeting in Phuket where she was presenting on her PhD research work examining the evolution of shell morphological characters, specifically on sculpturing. After her talk, we caught up for afternoon tea and she told me about a shell of Alathyria from a European museum collection that had nodular bumps on the umbo, but the taxonomy from McMichael & Hiscock 1958 indicated the shells were supposed to be smooth in the Velesunioninae. She asked me whether I had seen any shells of Westralunio carteri or other Australasian Velesunioninae species which had sculpturing. The problem is that after just a few years of development, the shell umbos erode so the original state of the shell is lost. So I set about looking at museum collections and specimen vouchers from CALM biodiversity surveys. The result was the astonishing discovery that Westralunio carteri had very distinct “wrinkled” sculpturing in juvenile shells (<20 mm long), but Velesunio wilsonii and Lortiella froggatti were smooth. The work was published by Zieritz, Sartori & Klunzinger in 2013. Looking at the glochidia is also intriguing (see Jones et al. 1986, cited in Klunzinger et al. 2013 https://doi.org/10.1080/13235818.2013.782791 as listed above). Turning over stones to look where others haven’t is, for me, the curiosity and joy of scientific discovery. ~ Michael Klunzinger

Week 52: WILLIAM LEWIS MAY AND THE MSA

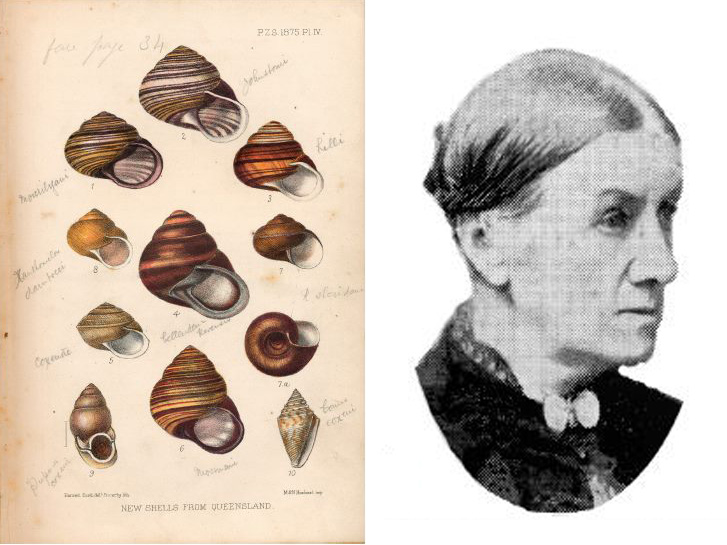

Biographies on the eminent Tasmanian conchologist William Lewis May are given by the late Margery Murray, Victorian MSA member (read to the Society on 25 May 1959, published in the MSA’s Australian Newsletter Vol. 7(27) October 1959, p. 7, and reproduced in the Victoria Branch Bulletin, 2006, no. 235, p. 6), and Ron Kershaw (published first in hardcopy in the Australian Dictionary of Biography, 1986, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University and available here. May was born in South Australia, but with his family moved to Tasmania during his early teens. He had many interests, among which were shells – on these he built up an impressive expertise and collection. He named many species, many of these being micromollusca.

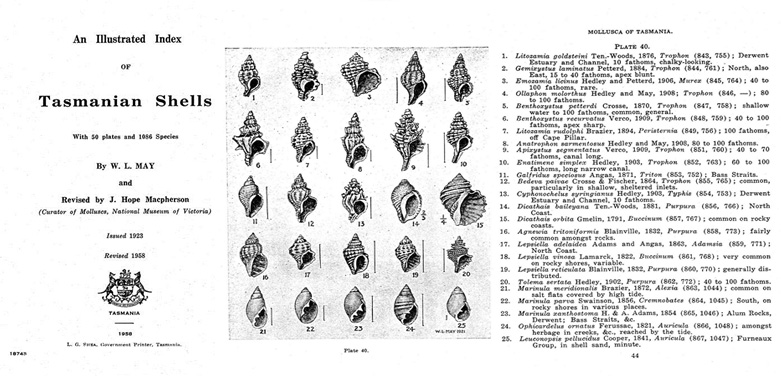

May is likely familiar to MSA members as the author of the important works, “A checklist of the Mollusca of Tasmania” (1921, Government Printer, Hobart) and, in 1923, the supplementary work, “An illustrated index of Tasmanian shells” (Government Printer, Hobart) with 47 plates of illustrations (done by May himself) and covering 1052 species. This included every then-known shelled mollusc in Tasmania -marine, freshwater and terrestrial.

Although May died at age 64 in 1925, his story intersects with the MSA in the 1950s when J. Hope Macpherson, a founding member of the MSA and former Curator of Conchology at the National Museum of Victoria, was asked to revise his illustrated index. The revised “An illustrated index of Tasmanian shells” was published in 1958 (Government Printer, Tasmania) with 50 plates of illustrations (retaining May’s 47 original plates and adding three more) and covering 1086 species. Although many new species have since been added to the Tasmanian list, May’s work remains valuable and relevant to the study of mollusca from the south eastern Australian region

~ Platon Vafiadis

Week 51: MALACOLOGICAL CABINET OF CURIOSITY AND WONDER

With this initiative, we aim to highlight marvelous molluscan diversity, unique adaptations and conservation opportunities for the Australasian malacofauna. We have assembled our list of 5 molluscan candidates/candidate groups to kick things off. It is unabashedly bivalve-centric:

1. Deepwater infaunal cuspidariids- Carnivorous bivalves. These bivalves possess a specialized septibranch gill that is modified into a septum (diaphragm) that is used to suck in cumaceans or small crustaceans from the water column. Many representatives have sensory papillae at the end of the siphon that sense movement.

2. Galeommatoideans- Small white flecks of bivalve dust. The group includes symbiotic bivalves that are modified to crawl like snails with their valves splayed open in the burrows of host mantis shrimp (e.g. Ephippodontomorpha spp.) and/or hang on to the esophagus of sea cucumbers (e.g. Entovalva spp.)(Middelfart 2005, Middelfart unpublished).

3. Tridacna and Hippopus – Giant photosymbiotic clams. These molluscs are larger than life, techni-color hybrids. Like corals, giant clams harness sunlight through the association with tiny microalgae called Symbiodinium entrained in their soft tissues. The mantle of giant clams is stunning and the color is attributed to the presence of the tiny algae (Kirkendale & Paulay 2017).

4. Clavagellidae – Watering pot clams. Members of this diverse group must be seen to be believed! The calcareous watering pot structure, with perforated holes buried in the sediment that permits water intake, is secreted by the tiniest of bivalves. This family is most diverse in Australia (Morton 2002).

5. Lithophaginae– Date mussels. Members of this group, including Lithophaga teres shown here, bore into live coral and also dead substrates through chemical and physical means. They are elongate and often go unnoticed by divers and reef walkers. Work that began in partnership with the late Barry Wilson is ongoing in WA to test relationships among mussels in this group and also track their association with different substrates.

Images are Cuspidarid showing long tube-like posterior extension of the shell that assists in suctorial feeding,Tridacna from Rowley Shoals, Lithophaga teres from inshore Kimberley. ~ Lisa Kirkendale and Peter Middelfart

Week 50: MOLLUSCS AS MODELS FOR CHEMICAL MAPPING TECHNIQUES

Throughout history molluscs have been a treasure-trove for the discovery of dyes and traditional medicines, and even now still contribute to modern/ current medicines. The unique chemical structures that make up these dyes and medicines are often synthesised in specialised organs or tissue regions within mollusc tissues. This “localisation” has enticed researchers to develop methods that can map these chemical structures directly from the tissues itself, to better understand the biosynthetic pathway that leads to unique dyes and medicines. The first test case was the Australian predatory whelk, Dicathais orbita. Chemically mapping structures in D. orbita also had the advantage of shedding light on how these structures function in the mollusc itself, for example, metabolites that are only expressed in a particular region during mating could be implied to be related to reproduction. Further exploring this pathway, these mapping techniques are now being applied to disease models where mollusc medicines are the cure, showing the distribution and metabolism of drug candidates in colorectal cancer and acute lung injury mouse models.

Through an unusual collaboration between malacologists and material scientists, researchers from SCU and Monash University are now mapping mollusc medicines in a variety of tissues and have adapted these methods to a variety of species. These mapping tools are expanding, also currently being used to track environmental pollutants and pesticides in invertebrates, to provide precise data on the metabolism of pesticides after contaminations events. Image adapted with permission from Ronci et al., Anal. Chem. 2012, 84(21) pp 8996-9001 (Copyright 2012 American Chemical Society). ~ David Rudd

Week 49: AUSTRALIAN MOLLUSCAN FISHERIES, A RESOURCE WORTH PROTECTING

Major fisheries exist in Australia for abalone, scallops, and squid, however we also harvest lesser-known species such as venus clams, vongoles, and trochus. Together, molluscan fisheries are worth approximately $170 million annually, and the industry provides employment for over 7,000 people, many of whom live in regional areas. (Source: Australian Fisheries and Aquaculture Statistics 2015; ABARES).

Assessment of the status of Australia’s key fisheries is undertaken every second year and reported in the ‘Status of Australian fish stocks’, currently produced by the Fisheries Research and Development Corporation. The status of each fishery (sustainable, recovering, depleting, overfished, or environmentally limited) is assessed by different methods depending on the species. These include catch per unit effort trends, biomass surveys and estimates, and recruitment and population surveys. Assessments for each species are often broken down into geographically separate fisheries – thus the same species can be assigned multiple status classes. For these species it is even more important to assess the source of the product in order to make informed decisions about responsible consumption.

There are multiple resources available to all of us to help us make the best choices regarding our seafood. For more information, check out the 2016 report or download the Sustainable Seafood Guide App .

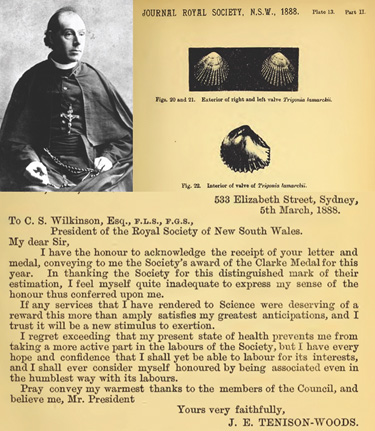

Week 48: REVEREND JULIAN TENISON-WOODS

Father Julian Tenison-Woods (1832-1889) was a missionary priest best known for co-founding the Congregation of Sisters of St Joseph of the Sacred Heart at Penola in 1866, with Sister Mary MacKillop. However, Tenison-Woods was also a scientist, and made extensive observations on Australian geology, palaeontology, botany and zoology. Throughout his life he described over 140 fossil and 280 recent molluscan species, many of which are now synonymised. Tenison-Woods’ scientific work extended beyond pure description, and included attempts to synthesise and correlate his observations with the unique Australian environments that he explored. In one of his last works, On the anatomy and life history of Mollusca peculiar to Australia, he writes, “The Molluscan character of any portion of the Australian coast differs according to its climate and situation. In no country perhaps in the World, are there more long stretches of low sandy coast, without rocks or indeed anything but sand-dunes… A few bivalve shells are scattered along the sand-dunes, the species varying according to the locality…In places where the shore is rocky, there is a complete change in the fauna. Within the tidal-marks, but generally in the highest part of them, we find a Patella outside the tropics, and a Nerita within tropical regions, though Patellidae are not wanting also…”

His observations and scientific mind also lead him to accept Charles Darwin’s views on evolution, and he concluded ‘I can well believe that there is much truth in evolution. If tomorrow the evidence of its occurrence were established on indubitable grounds, it would be one more beautiful illustration of the plan of nature’. These views, i.e., of theistic evolution, were perfectly consistent with those of the Roman Catholic Church at the time.

For more information, please see:

– King, R.J. (2016). Julian Tenison Woods: natural historian. Proceedings of the Linnean Society of New South Wales. 138, 49-56.

– The Malacological Society of Australasia Victoria Branch Bulletin No. 232 (February/March 2006) https://www.malsocaus.org/docs/vic/bulletin/Bulletin%20232.pdf

Image from http://www.tenison.catholic.edu.au.

Week 47: MSA CONFERENCES

For many MSA members, one of the highlights is our triennial conference. During this time, a group of scientists, students, and enthusiasts get together for a few days to share the latest malacological research. This includes formal scientific presentations, but the conferences are also notable for their dynamic and inclusive atmosphere which tend to foster a lot of fun and interesting discussions, not to mention some funky dance moves. We also organise field trips and activities to showcase the local environment, including diving trips and bushwalks. MSA Honorary Member Winston Ponder points to the many tangible outputs stemming from his experiences at these conferences and notes the vital participation of students.

The MSA conferences are a relatively recent phenomenon, starting with Molluscs 1997 on Rottnest Island. This conference attracted 60 experts from Australia, New Zealand and 11 other countries – over half of the delegates were from outside of Australia! This conference had a large overseas turnout because the world malacological group UNITAS only held their conferences in Europe until 1998. Since then, the conferences have been held in Sydney (2000), Perth (2004 as the World Congress of Malacology, organised by Fred Wells), Wollongong (2006), Brisbane (2009), Melbourne (2012), and Coffs Harbour (2015). More details of the conferences can be found here. ~ Rachel Przeslawski

Week 46: SEA SLUG CENSUS

Citizen scientists have made a remarkable contribution to the documentation of the world’s mollusc species, mostly through the collection of shell specimens which now form an important component of museum collections. More recently, the availability of affordable underwater cameras has also provided the opportunity for volunteers to gather images from which important data can be extracted.

Sea slugs are highly popular subjects for recreational, underwater photographers whose images consequently represent a potentially important record of patterns of species diversity and distribution. Most sea slugs have rapid life cycles (<1 year) and specific habitat requirements which means that populations, and whole assemblages, may quickly respond to changing environmental conditions. This suggests that they have considerable potential for monitoring human-induced changes, including climate change.

The Sea Slug Census (SSC) program was established by Southern Cross University as a way to harness this enormous potential to document species distributions and to explore pathways for ongoing, volunteer-based biodiversity monitoring. Starting in Nelson Bay in December 2013, with support from the Combined Hunter Underwater Research Group, and NSW Department of Primary Industries (Fisheries), the program is now running at 4 locations in NSW, and 1 in QLD, with additional venues planned for the near future. The 22 SSC events to date have engaged over 300 divers, snorkelers and rock-pool ramblers who have documented new regional records and at least 30 poleward range extensions, many of which have now been formally documented in the peer-reviewed literature. Observations from NSW also form part of the framework for the first illustrated inventory of sea slugs in NSW (available at http://www.publish.csiro.au/RS/RS16011)

Examples of key discoveries include (see images): the first Australian record of Doriprismatica paladentata during the 2017 Gold Coast Sea Slug Census; the identification of Nelson Bay, NSW, as a global hotspot for sea hare diversity through successive SSCs since 2013; rediscovery of the Macleay’s Spurilla (Spurilla macleayi) at its type locality in the Sydney Sea Slug Census, 2016. ~ Steve Smith

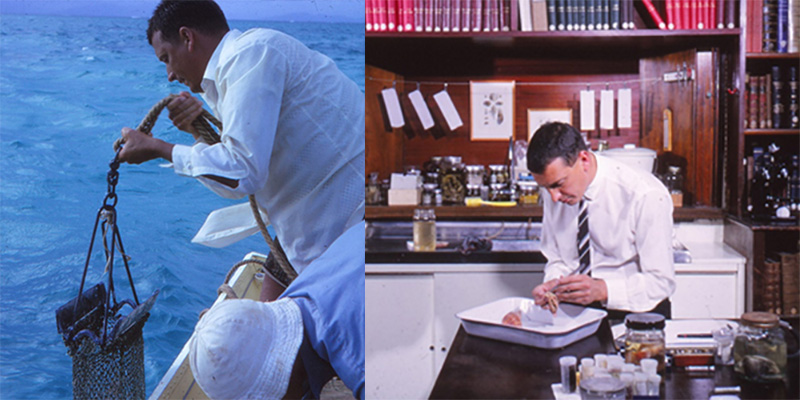

Week 45: DR DONALD FRED MCMICHAEL, CBE

Born in Rockhampton in Jan, 1932, Don McMichael spent most of his early life in Sydney. He was awarded a cadetship at the Australian Museum in the Mollusc Department in 1948 and graduated from the University of Sydney in 1952, when he was appointed Assistant Curator of Molluscs (under Joyce Allan). He obtained a Fulbright Travelling Scholarship and did his PhD at Harvard University with his thesis on Australasian freshwater mussels. He published this work (with Ian Hiscock) in 1958 and a number of papers on volutes, land snails and freshwater molluscs. He also authored two popular books on Australian marine molluscs and undertook field work in New Guinea, and various parts of Australia, notably the in tropical Australia. Don became Curator in 1956 when Joyce Allan retired and, briefly, Deputy Director of the Australian Museum in 1967, shortly before he left the museum to pursue his interests in conservation, becoming the first director of the Australian Conservation Foundation and later taking up other important administrative posts in both the NSW and Commonwealth Government. He was active in the Malacological Society of Australia being Secretary-Treasurer from 1965 to 1968 and President in 1969 and he also edited the Journal of the Malacological Society of Australia (now Molluscan Research) from 1961 to 1968. Don’s numerous outstanding post-museum service and achievements were recognised 1981, by his being made a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) for public service, and in 2001 he was awarded a Centenary Medal for contributions to Australian Society. Don died on the 10th June, 2017 and is survived by his wife Helen, his two children Susan and Janet, and three granddaughters.

A fuller account of Don’s malacological contributions (including a bibliography and list of his new taxa) can be found here. ~ Winston Ponder

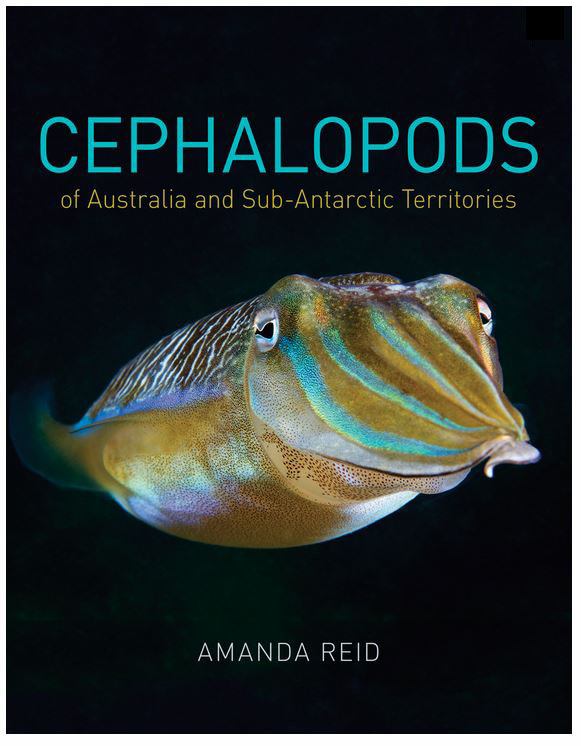

Week 44: CEPHALOPODS OF AUSTRALIA

It’s no surprise that cephalopods are often considered the most interesting group of molluscs – they’re colourful, expressive, mysterious, and have some quirky behaviour sometimes missing from their less intelligent relatives. Australia has the highest diversity of cephalopods, from the southern pygmy squid (Idiosepius notoides) to the largest species of cuttlefish in the world (Sepia apama). Cephalopods of Australia and Sub-Antarctic Territories by Dr Amanda Reid compiles all of these incredible animals into a single volume that represents over 25% of the world’s cephalopod species. Released in 2016, the book includes keys, species descriptions, colour illustrations, and distribution maps for 226 species and is therefore invaluable as a field guide. As pointed out by Bronwyn Gillanders in a review of the book, “the book will be especially valuable to systematists as the complete reference as the original species description, type repositories and type localities are provided for each species”. It also contains summaries of biology, behaviour and related fisheries so will appeal to anyone with an interest in these amazing animals.

Author Mandy Reid is the Collection Manager of Malacology at the Australian Museum and a long-standing member of the MSA (as well as our former Newsletter Editor). We congratulate her on the publication of the premier cephalopod resource in Australia! ~ Rachel Przeslawski

Week 43: PERFECTING PEARLS

The innate beauty of pearls has enticed human beings throughout history. Although naturally formed pearls are rare (and, by extension, expensive), the development of pearl culturing techniques means that these biologically-produced gemstones are no longer exclusively for the wealthy. Cultured pearl formation involves the implantation of a small piece of oyster mantle tissue (the graft, or ‘saibo’), and a round nucleus, into the gonad of a host oyster. The saibo will then grow around the nucleus and direct the deposition of calcium carbonate on to its surface to produce the pearl. Unfortunately this process does not always go smoothly, and pearl producers are faced with a proportion of their crop that is substandard (sometimes downright ugly!) and of low worth. To try to improve this, a number of Australian pearl producers have partnered with researchers at various universities (including JCU, UQ and USC) to better understand and improve the pearl formation process. The research has included carefully designed experiments to identify the biological and environmental factors that influence pearl formation, leading towards changes to pearling operations and animal husbandry that improve pearl quality. More recently, research efforts have turned to advanced genomic and transcriptomic techniques to understand pearl formation at the molecular level. As a result, significant genetic resources exist for Australia’s favourite pearl oyster, Pinctada maxima, including exhaustive mantle and pearl sac transcriptomes and a high density genome-wide SNP map, meaning that this oyster is one of the most ‘genetically tooled’ marine invertebrates. Although these resources have, and will continue to, help improve pearl quality, they also provide basic knowledge into how organisms can fabricate exquisitely engineered biological structures with properties that often far exceed those of humankind’s most advanced materials.~ Carmel McDougall

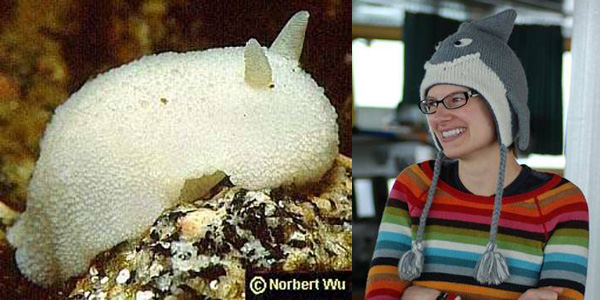

Week 42: ANTARCTIC MOLLUSCS AND NERIDA WILSON

Phylogeography requires replicate sampling of common species across a wide canvas to test hypotheses about the spatial distribution of genetic diversity. This can be difficult even in the best cases, such as relatively accessible ecosystems, like shallow-water coral reefs or montane cloud forests. But can you imagine being bold enough to attempt phylogeography in frigid, remote, deep-sea waters off Antarctica, which requires complicated and expensive logistics for sampling, is constrained by massive weather systems and involves coordination for permits across many countries? Nerida Wilson can and did! She has been instrumental in demonstrating the level of marine cryptic species complexes in Antarctic waters, testing the circumpolar distribution paradigm with molecular data, and using interdisciplinary approaches to show how Antarctic diversity may have been generated for many years. While Nerida began her career using histology to recover phylogenetically conserved characters at UQ with John Healy, she then moved to incorporate molecular data to help understand the evolutionary history of organisms and has continued in this vein ever since. Nerida has participated in numerous deep sea and Antarctic expeditions, using traditional methods and Remotely Operated Vehicles to obtain samples. She dived in the submersible HOV Alvin in 2005, diving on unexplored vents on the Pacific-Antarctic Ridge (>2500m) and in 2010, she led the cruise that recovered large numbers of Monoplacophora for molecular and phylogenomic analysis off California. To date, she has deployed to Antarctica seven times, acting as Chief Scientist for two of those cruises. She co-authored the proposal for the 2012-2020 SCAR Biology Scientific Research Programme “State of the Antarctic Ecosystem (AntECO)” to promote international interdisciplinary research relevant to Antarctic ecosystems and was also involved in a WikiBomb to support Women involved in Antarctic Science. In 2014, Wilson was awarded an Antarctic Service Medal from the United States Antarctic Program. Based in Western Australia at the WA Museum, she recently received funding to participate in the Antarctic Circumnavigation Expedition (ACE) program funded by Swiss Polar Institute to test phylogeographic questions across multiple invertebrate taxa in the sub-Antarctic islands. Her favourite Antarctic mollusc, of course a nudibranch sea slug, is Doris kerguelenensis, (pictured, aka the coconut snowball), part of yet another never-ending species complex. ~ Lisa Kirkendale and Kara Layton

Week 41: TAKING MALACOLOGY TO THE MASSES

This year (2017) the Malacological Society of South Australia (MSSA) continued our tradition of exhibiting at the three day “Science Alive” fair in Adelaide as part of the annual National Science Week. Our exhibit theme “Molluscs of the World” was visited by many thousands of young would be scientists and their families. The “Science Alive” fair has become increasingly popular since its inception, and in 2017 an attendance record of over 30,000 visitors was achieved. The first day of the event is dedicated to a Careers Day specifically for students and teachers from all parts of the state, with the subsequent two days open to the general public. This year the organisers expanded the event by including several regional Science Alive fairs and an inaugural Environment Fair. The MSSA’s aim is to improve the public’s general knowledge of marine environmental issues while highlighting the beauty and diversity of molluscs. This year the MSSA assisted the newly formed “Port River Shell Reef Restoration Group” with their exhibit related to restoring the oyster population back into the Port River system. They are a new community group associated with the local Estuary Care Foundation and council authorities.

In the last five years the following MSSA themes have been well received and we have learned much about the public’s perception of all things molluscan.

2013 – Slugs and Snails SA. Our display highlighted the problems of the introduced pests while showcasing the little known native land snail species. We promoted a local snail and slug survey and discussed the issues of pest control.

2014 – Mega Molluscs. – A vastly more engaging display of our biggest and best, from huge fossil ammonites on loan from the University of Adelaide, Geology section, to models of giant Cuttles and squid on loan from the SA Museum, to the giant clam Tridacna maxima and the golden trumpet snail Syrinx aruanus of the north coast.

2015 – Molluscs : Light and Colour. – (Science’s International Year of Light) A display based on pigmentation of shells, colour perception underwater, the evolution of molluscan eye morphology, pearls and pearl shell, the properties of iridescence, and physics of light refraction and fluorescence.

2016 – Beachcombing in SA. This engaging display showcased the wealth of molluscs that live along our local shorelines. We engaged with the public on issues such as fishing, the current laws surrounding beach collecting of shells and the importance of our marine reserves. The display featured a variety of anthropogenic material that washes up after winter storms, e.g. clothing, containers, industrial waste, etc. with the most notable item being large numbers of plastic screw on bottle tops. In SA we recycle cans, plastic and glass bottles, but discard the top that was supplied with them, creating an environmental problem.

2017 – Shells from around the World. A more general display featuring shells from our main bioregions, with specimens from both the tropical and temperate waters of Australia and overseas.

Many thanks go to all of the MSSA team for all their efforts over the last five years. ~ Peter Hunt

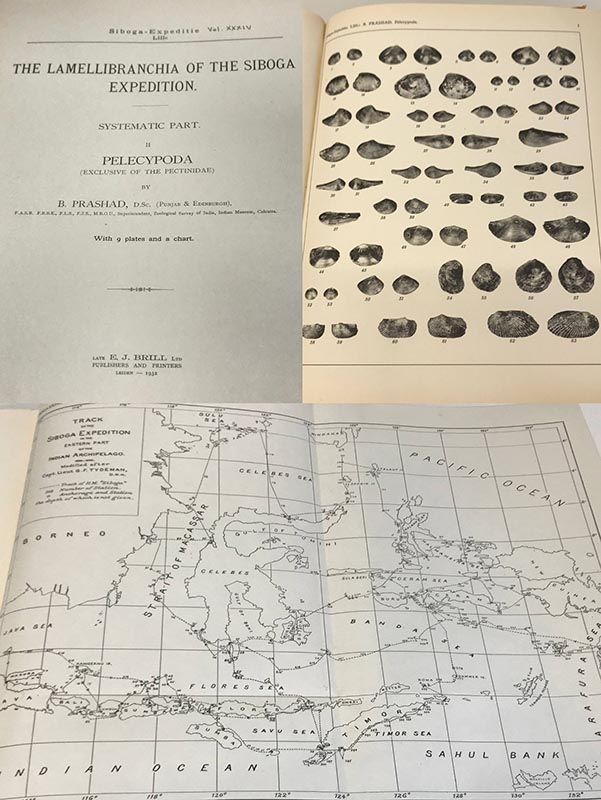

Week 40: MALACOLOGICAL LIBRARY OF AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM

When I started working at the Australian Museum in Sydney one of my favorite parts was the malacology library. I had never seen such a functional and comprehensive library in one place. There were many impressive, almost unfathomable parts to it. With a key I could go under the stairs and select from a huge range of very rare books, and hardly ever did I go in there without exiting with the volume of book I needed, some dating back hundreds of years. Of course that would later be relocated to the main library and spread out and not be as accessible ever again. But for me it was a great mind expanding trip of molluscan discovery and a possibility to browse books for hours. I would sit on the stool in there and read and read and be amazed by how much work was accomplished in times of wars, famine and disease.

Another part to the malacology library was the looseleaf folders. All possible information, in the form of articles, newspaper prints, hand written comments from over 100 years were complied in scrapbooks. So if you needed to know about a particular mollusk species, a synonym, a malacological personality – you could search the card index or go to the shelves and find all about it. Once I understood the layout and idea behind the library I felt that someone from the past was lending me a hand to understand and further the knowledge of Australian malacology.

This library was in part the brain child of Charles Hedley who collected and donated books to the AM. His notes are found everywhere, and good ones, notes on particular species from Paris, London etc. He was very productive. Transferring all this work from Hedley’s notes to the loose leaf system was mostly a contribution of Winston Ponder and the numerous staff (Ian Loch, Phil Colman, Alison Miller, Janet Waterhouse, Bill Rudman, etc) and many volunteers. Starting it was an enormous effort and Winston told me how he would have all the notes, articles, snippets of information spread over the floor at home and slowly build this system – family would help in the cutting and gluing. I talked to the volunteers every week who were still incorporating new information in these loose leaf folders back in 2004.

For me this library was essential for working on revisions and developing the catalogues and directories of Australian marine molluscs (Biotic Database of Indo-Pacific Marine Molluscs for OBIS and Australian Fauna Directory for ABRS). Once you have worked on a group of molluscs in the AM collection and used the facilities there, it is hard to imagine working anywhere else given the support of this system.

Of course nothing is forever and bureaucracy and the digital age have now taken over this wonderful asset. Accessing a rare book now is close to impossible and is best done via Biodiversity Heritage Library (BHL). But that means no more browsing or handling great works, and for me, gone is much of the charm of discovery. Of course there are huge benefits, like search engines. I can now find a species name in an old book of eg. Lamarck in seconds – if it has been scanned and OCR’ed. Another impressive malacological library is that in Paris – just wonderful! Images from the Siboga Expedition volumes (bivalves of course!.~ Peter Middelfart

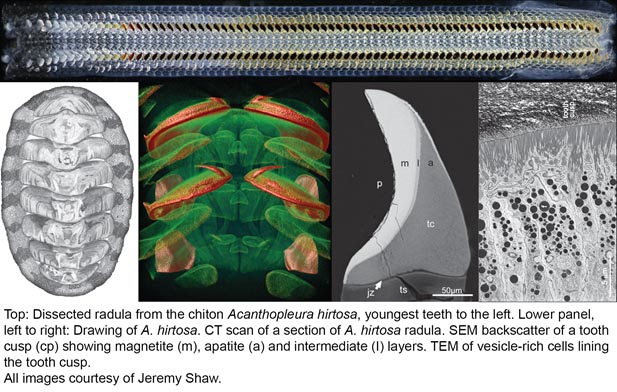

Week 39: RADULA, THE STRONGEST KNOWN BIOLOGICALLY-PRODUCED MATERIAL

Surviving on algae living on and within rock is a tough way to make a living, and requires even tougher teeth! Some molluscs, including chitons and limpets, have made rock-scraping a reality by evolving a complex radula in which constantly replaced tooth cusps are impregnated with iron biominerals. Jeremy Shaw (University of Western Australia) and colleagues have provided fascinating insight into the high performance of these teeth by using advanced microscopic techniques to study their ultrastructure. They have shown that the chiton radula tooth is comprised of three main sections: iron oxide magnetite on one side, calcium apatite on the other, and an intermediate layer consisting of two types of iron oxyhydroxide; goethite and lepidocrocite. These minerals are deposited via the action of specialised, vesicle-rich cells found adjacent to, and in a canal within, the developing tooth structures. The team also found that the interfaces between the different layers of materials are highly intercalated, which may explain why the teeth do not fracture along these interfaces in stress tests – a property that materials scientists are very keen to emulate. ~ Carmel McDougall

Week 38: MOLLUSCAN CLIMATE CHANGE RESEARCH OF RACHEL PRZESLAWSKI

As part of her PhD research at the University of Wollongong, Rachel Przeslawski undertook some of the first investigations into the impacts of climate change stressors on molluscan encapsulated development. Firstly, she demonstrated the significant detrimental effects of exposure to ultraviolet radiation, depending on the habitat in which species lay their egg masses: species adapted to lay in full sun intertidal habitats were more resistant, whereas those that lay in shade or partly shaded habitats suffered significant mortality (Przeslawski et al. 2004). She then designed a complex multifactorial experiment to investigate the potential synergistic impacts of multiple climate change stressors. This involved applying 27 treatment combinations of salinity, temperature and UV radiation to the egg masses of three intertidal molluscs (Przeslawski et al. 2005). The results showed significant synergistic effects, with increased mortality and retardation in development under the most physiologically stressful conditions. In particular, exposure to UVR caused a 12-fold increase in mortality under elevated temperature and salinity conditions, even for species such as Bembicium nanum and Siphonaria denticulata that are adapted to lay egg masses high on intertidal rock platforms in the full sun. This study demonstrates that the ecological impacts of climate change can be greatly underestimated if the impacts of environmental stressors are only studies in isolation. Rachel’s foundational study highlights the importance of considering the complex interactions between multiple stressors in climate change studies and has now been cited well over 100 times. ~ Kirsten Benkendorff

Week 37: PROFESSOR RALPH TATE

Professor Ralph Tate was an eminent, if not at times controversial, naturalist who made significant early contributions to the understanding of Australian malacology (both recent and fossil), botany and geology. In 1875 the recently established University of Adelaide sought the recruitment of key British academics to ensure that degrees were recognised outside the colony. Tate delightedly accepted a position in 1875, and within three months had arrived in Port Adelaide to prepare for the University’s first degree course in natural science and chemistry, which began in March 1876. Although revered by his students, Tate had regular clashes with the University Council, often due to his participation in non-university work and expeditions. It was during these expeditions, however, that Tate made many of his most significant collections. These were held within the University Museum that he fought hard to establish. Although the majority of these collections, including his shells, are now housed elsewhere, the University of Adelaide’s Tate Museum is currently one of the largest geology museums in Australia.

Image below left: Ralph Tate [from Australian Botanic Gardens]; below right: Cover inset of A Manual of the Mollusca by SP Woodward (1875) .

Week 36: FIRST MSA PRESIDENT

Denzil Hartley was the first President of the MSA, serving from 1956 – 1964. Prior to the formation of the MSA, he was also a Foundation Member of the Malacological Club of Victoria which was formed in his home. He was a successful businessman with many friends in commercial and political circles, but he actually made no claim to being an expert on molluscs. Instead, he came to malacology through his wife Thelma’s interest in shell collecting and accompanies her on many excursions. His ardent concert for the MSA and his hospitality seem to be the main drivers for the increase in members during his tenure. His memorial notice in the Australian Newsletter of the MSA (vol 13, 1965) describes him as a ‘warm, friendly man with a wonderful knack of making you feel completely at home so that afer a short acquaintance you felt you had made a life-long friend’. ~ Platon Vafiadis

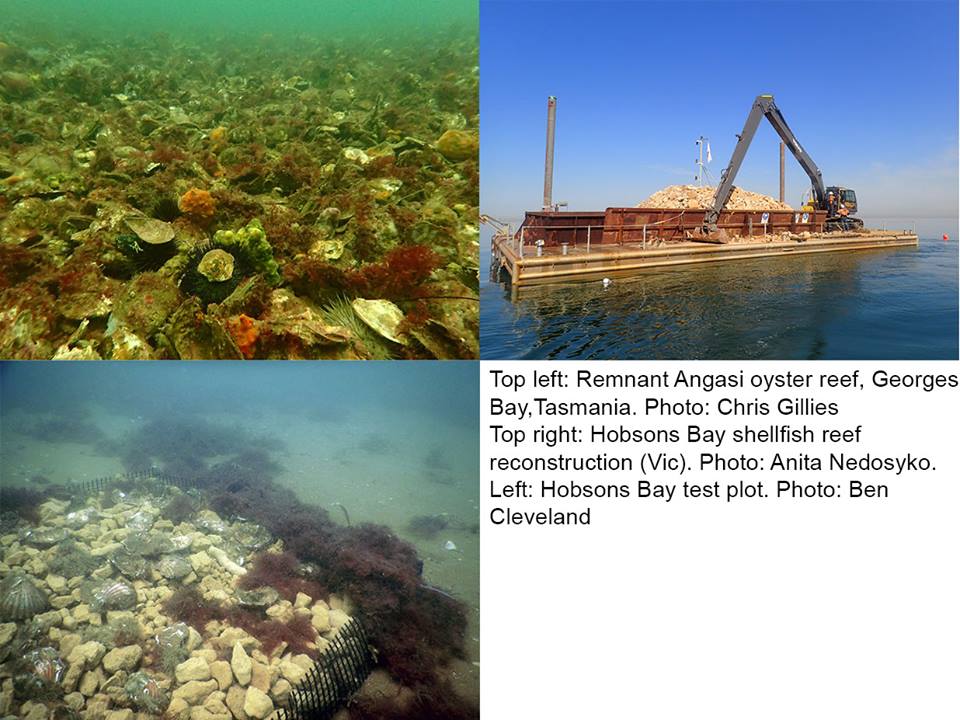

Week 35: THE HUMBLE OYSTER: AN ECOSYSTEM SAVIOUR

For most people, the word ‘reef’ conjures images of colourful marine creatures of all kinds, living amongst a backdrop of spectacular coral species. One hundred years ago, however, it is likely that reefs of a very different nature sprang to mind. “Shellfish” reefs, formed by oysters or mussels and built up over time, were once extensive around much of Australia’s coastline and were an important source of food for its rapidly growing population, and of lime for the booming construction industry. Today, only a small fraction of these reefs remain – a likely result of a number of factors including overfishing, increased nutrient runoff, and increased susceptibility to disease.

Shellfish reefs perform a number of functions, including providing habitat and spawning grounds for other species, protecting coastlines from erosion, and maintaining water quality by filtering. The re-establishment of shellfish reefs has become an area of increased focus around the world, including in Australia. The Nature Conservancy, an international environmental agency, has been driving several restoration initiatives in Port Phillip Bay, Gulf St Vincent and Albany, and additional projects are also occurring in Queensland and New South Wales. These projects are already showing great promise for revitalising functionally-extinct oyster reefs, providing rejuvenated habitats for a range of marine species. ~ Carmel McDougall

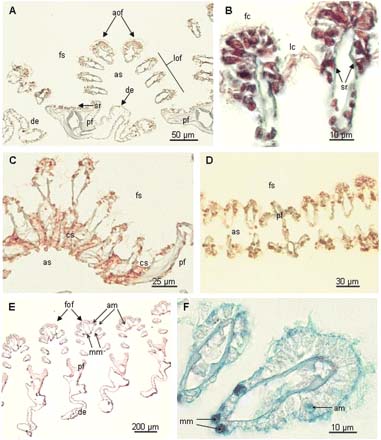

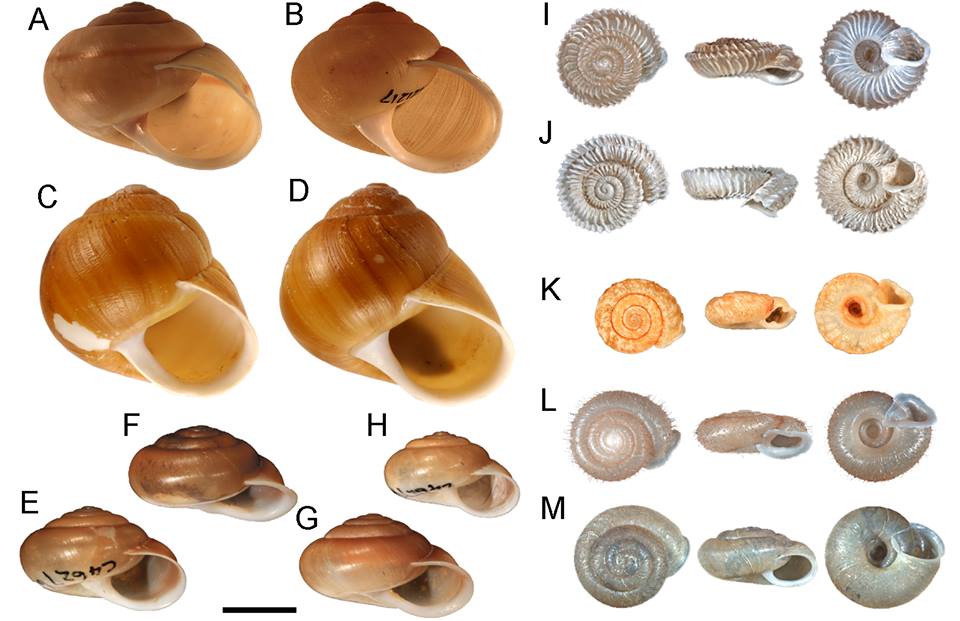

Week 34: CAMAENID LANDSNAILS EXHIBIT MORPHOLOGICAL CONVERGENCE

Land snail diversity in Australia is highest in the tropical areas, particularly eastern Australia where over 44 families and 800 species have been recorded (Stanisic et al 2010). Solem and other earlier workers (e.g. in publications spanning 1979-1997) revealed that the land snail fauna of north-western and central Australia is dominated by one family, the Camaenidae, a pattern not generally observed in the eastern Australian tropical land snail fauna. Although studies are few, members of the family, have developed adaptations (such as aestivation, surviving extended droughts, ability to absorb water from non-saturated air, shell permeable to water, adaptation to high temperatures) that enable them to occupy near deserts. Synthetic work by Köhler and colleagues over a decade (beginning with Köhler 2010a. in Molluscan Res. 30, 1–16.) has revealed the true magnitude of this marvellous endemic radiation and begun to examine how such diversity evolved. Together, the work has involved survey of 22 large islands from 2007-2010 (the Kimberley Islands Project), with later surveys tackling middle and eastern areas, including more arid parts of the top end. More than 300 species in 41 genera are now known with northwestern Australia considered one of the ‘hottest hotspots of camaenid diversity in Australia’ (Köhler and Criscione, 2015). Enhanced molecular phylogenetic dataset with high taxon sampling has highlighted widespread convergence of all studied shell traits and three out of four genital features. Results point to repeated instances of convergence in a suite of morphological and anatomical characters among unrelated clades and confirm that snail shell and anatomy are poor guides for higher-level classification. The authors suggest that increasing aridity, against a backdrop of structural constraints, has influenced the evolution of these land snails.~ Lisa Kirkendale, Corey Whisson, Frank Köhler

Week 33: NUDIBRANCHS ENCYCLOPAEDIA: THE WORK OF THE LATE NEVILLE COLEMAN

Neville Coleman started keeping species lists at the age of 10 … and never stopped until his untimely death in May 2012. He was highly influential in the documentation of Australian marine life, educating both the diving and wider communities about this extraordinary diversity.

“Give me a puddle of mud to dive in and I’ll find something to photograph” (Neville Coleman – 1976 New Zealand Oceans conference). His tenacity and dedication resulted in the discovery of more than 450 marine species with at least 24 named in his honour, the most recent being the extraordinary Melibe colemani Gosliner & Pola, 2012.

His legacy includes over 50 publications, with the first hitting the bookshelves in 1974. Neville loved molluscs and produced many works providing information on their collection and identification, whilst adding important specimens to museum collections. He had a particular passion for sea slugs and, teaming up with Dr Richard Willan, published the first book specifically on Australian nudibranchs in 1984. This passion led to the most comprehensive work covering the Australian and Indo-Pacific sea slug fauna, the Nudibranchs Encyclopaedia (2008) which was reprinted and revised as part of his legacy in 2015. Building on an earlier work (1001 Nudibranchs, 2001), which utilised selected photos from a collection of more than 70,000 images, taken both by himself and numerous other underwater photographers, Nudibranchs Encyclopaedia is a dazzling introduction to the ‘butterflies of the sea’. It is a pleasure simply to marvel at the colour and form of these extraordinary molluscs. For many experienced field malacologists, it remains a valuable reference, annotated, dog-eared, but always in use or at eye-level on the shelf.

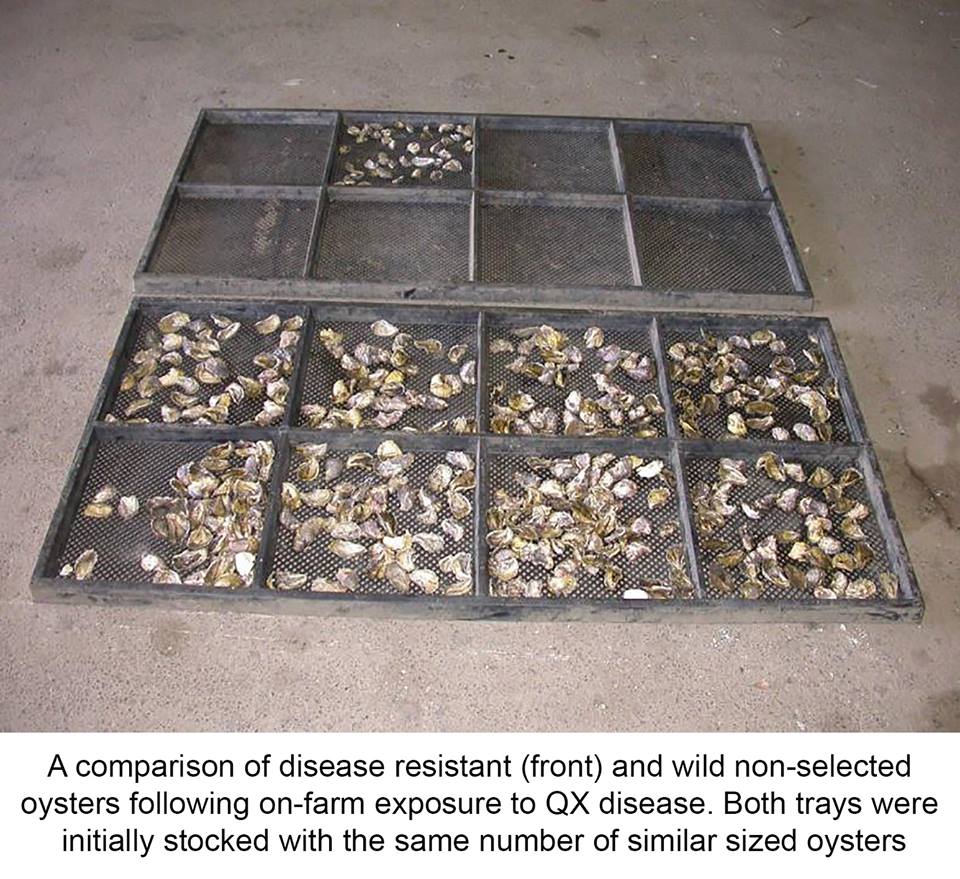

Week 32: A SUCCESSFUL SELECTIVE BREEDING PROGRAM FOR OYSTERS

The first selective breeding program for molluscs in Australia began at the Port Stephens Fisheries Institute in 1990. Initially targeting fast growing and disease resistant Sydney rock oysters (Saccostrea glomerata), the program was based on mass selection techniques to breed new generations from survivors of disease outbreaks. Great progress was made and oysters capable of growing over 30% faster and surviving disease outbreaks were provided to industry (Photo). Today the program continues, but?has evolved into a family-based program comprised of over 220 families that are assessed for a range of traits including growth, shell shape and meat condition through to disease and ocean acidification resistance. ~ Wayne O’Connor

Week 31: KIMBRELLA – THE OLDEST MOLLUSC?

It is widely believed that most extant animal phyla originated during the Cambrian explosion. Molluscs, however, may have been early bloomers! In the 1940’s a small fossil animal was discovered in late Precambrian rocks from the Ediacara Hills in South Australia. Originally described as a cnidarian, additional specimens were later unearthed near the White Sea in northern Russia. From these specimens, it was determined that Kimberella possessed a smooth, rounded ventral structure (interpreted to be a ‘foot’), surrounded by a concentric crenulated structure (interpreted to be a ‘mantle’). This, and scrape-like trace marks found in close proximity to the fossils (thought to be made by the action of a radula-like feeding structure), lead to the hypothesis that Kimberella in fact represents an ancestral mollusc. Although the animal did not possess a calcified shell, some reports indicate that it may have had a ‘hard’ dorsal plate. ~ Carmel McDougall

Week 30: NOT-SO-SECRET-SPAWNING OF GIANT CUTTLEFISH

The giant cuttlefish (Sepia apama) is arguably one of the most stunning invertebrates encountered by divers in Australia. This is probably due to its large size, expressive eyes, colour-changing ability, and camouflage behaviour. Research by Dr Mike Steer and colleagues has helped shed light on the life history of this amazing animal including its reproduction.

For unknown reasons, a relatively small area off the coast of South Australia is home to the world’s densest aggregation of spawning cuttlefish. Up to 250,000 cuttlefish converge on the region every year to fight, display, mate and die. The aggregations have become so predictable that there is now a burgeoning tourism industry around it. ~ Rachel Przeslawski

Week 29: A STALWART OF ZEW ZEALAND MALACOLOGY

In this post we would like to highlight the work of New Zealand’s preeminent malacologist Dr Bruce Marshall. Bruce is the Collection Manager of Molluscs at the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, and is the leading authority on the taxonomy and systematics of living molluscs in New Zealand. Since 1967 he has published more than 140 scientific papers on living and fossil molluscs, from both terrestrial and marine environments.

As collection manager of molluscs, Bruce is responsible for a vast collection of several million specimens representing more than 4,700 New Zealand species. It is estimated that nearly 2000 species of New Zealand mollusc remain undescribed. Bruce has done more than any other to reduce that number, describing and naming 584 species and genera to date.

In recognition of his work 24 species and 6 genera have been named after him, and in 2012 Bruce was awarded a Doctor of Science degree by Victoria University of Wellington for his exceptionally significant contribution to New Zealand molluscan taxonomy and systematics. ~ Simon Hills

Week 28: MALACOLOGIST WINS YOUNG AUSTRALIAN OF THE YEAR (SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY) IN 2000

In 2000, Dr Kirsten Benkendorff was honoured as the Young Australian of the Year in Science and Technology, making her the first (and so far only) malacologist to win this prestigious award. The award was based on research conducted during her PhD at the University of Wollongong, ‘Bioactive molluscan resources and their conservation: Chemical and biological studies on the egg masses of marine molluscs’. Using her combined expertise in chemistry and biology, Kirsten discovered more than triple the number of mollusc species previously recorded in the Illawarra region of New South Wales. Importantly, she also discovered a powerful and novel antibiotic in the eggs of some sea snails, including the dog whelk Dicathais orbita, research which is still continuing through her former students . Kirsten is now based at Southern Cross University where she continues to bridge biology and chemistry, focussing on the resource potential of molluscs as bioindicators, food, pharmaceuticals, and even art! ~ Rachel Przeslawski

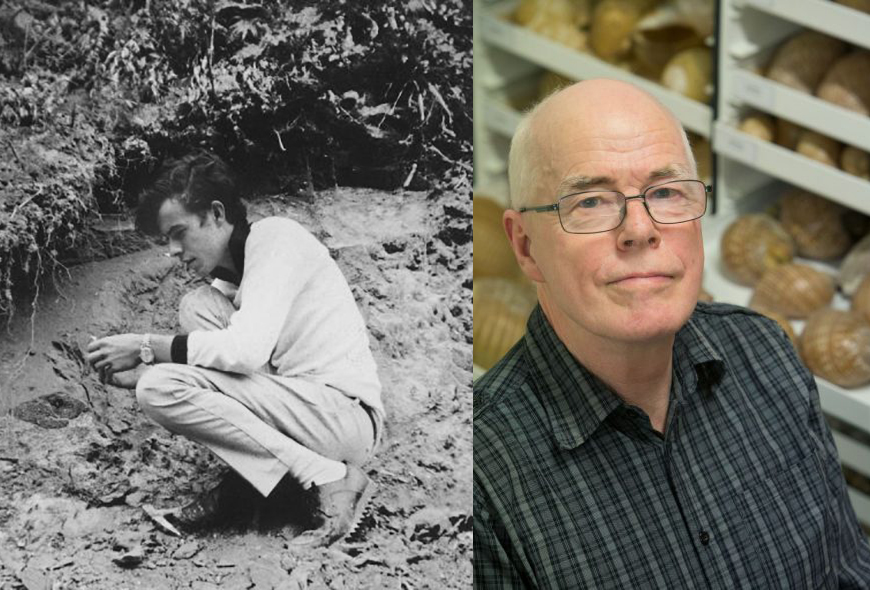

Week 27: PIONEER OF AUSTRALIAN MALACOLOGY

Dr Barry Wilson was born in coastal southwestern WA where he spent much of his childhood exploring the seashore and laying the foundation for his lifelong enthusiasm for marine molluscs. He received his PhD from UWA and undertook a postdoc at Harvard on molluscan systematics. During his career, he held a number of posts, including Curator of Molluscs at the Western Australian Museum. One of Barry’s key achievements is his impressive 2-volume work Australian Marine Shells in which he combines comprehensive details of the taxonomy and biology of Australian gastropods with stunning photographs and illustrations. Most malacologists and shell-collectors in the region will have their own well-thumbed copies of these books. His earlier work (e.g. Wilson and Gillett 1987) was just as pivotal and influenced a generation of molluscan biologists in Australia. His ability to weave taxonomy with biogeography to arrive at useful marine conservation guidelines was invaluable. Barry was one of the longest-standing members of the MSA, with records showing his membership dates from at least 1957 – over 60 years of involvement!

Week 26: CHROMODORIS NUDIBRANCHS IN THE INDO-PACIFIC

Chromodoris is a genus of nudibranch found in both shallow and mesophotic reefs in the Indo-Pacific. At one time this genus was the most diverse of all nudibranchs, with close to 300 species, but molecular work showed that Chromodoris was polyphyletic and in need of revision. Chromodoris now contains 22 described species that all have black pigmentation and lay flat egg masses (the only genus with flat egg masses in the ent…ire chromodorid family!). They’re a favourite of divers because of their bright and beautiful colours and because they’re often found feeding on equally beautiful sponges. These nudibranchs sequester toxins from sponges and store them in mantle glands along their body to use as a form of chemical defense against predators. Dr. Karen Cheney and her team at the University of Queensland are looking at chemical diversity in these nudibranchs and its implications for mimicry. In addition to this work, researchers from UWA, the WA Museum and California Academy of Sciences have found that some Chromodoris species mimic co-occurring congenerics on a regional scale. Vinicius Padula and colleagues at the SNSB-Bavarian State Collection of Zoology recently discovered a similar case of mimicry in two other chromodorid nudibranchs, Felimida clenchi and F. binza, which show different colour patterns across their range that are similar to the colour patterns of regional congenerics. This also means that although colour patterns have often been used to identify different species of chromodorid nudibranch, this character may in fact be unreliable. ~ Kara Layton

Week 25: GIANT CLAM RESEARCH IN AUSTRALIA

Giant clams (Tridacninae) are the heaviest living bivalves on the planet and when you are lucky enough to see them alive on the reef, the larger-bodied species resemble enormous underwater flowers with beautiful mantle coloration of variegated shades of blue, green and brown. The mantle especially is home to a wide diversity of photosymbionts (tiny algae) in the genus Symbiodinium that contribute to giant clam nutrition, similar to the partnership in corals. Tridacninae are not a particularly diverse cardiid subfamily (less than 15 species in two genera, Tridacna and Hippopus) but compared to most other molluscs they are very well studied, given utility in aquaculture, importance as subsidence food source in many island nations and high conservation value given illegal harvesting of many species (all species are CITES red-listed). However, even though our knowledge of giant clams is substantial, there are still surprises! Recent molecular work on the group in Australia, published in 2013, highlighted the occurrence of a new lineage, research led by Cynthia Riginos and her team at UQ. The lineage was then formally described by Penny & Willan in 2014 as Tridacna ningaloo (a name presently considered a junior synonym of T. noae). This species, almost morphologically indistinguishable from T. maxima (the elongate giant clam), is actually more closely related to T. squamosa (the fluted giant clam) and T. crocea (the boring giant clam). ~ Rachel Przeslawski

Week 24: MUSEUM REFERENCE COLLECTIONS PROVE INVALUABLE

Museum collections are vital to help document biodiversity, but they can also provide answers to future questions that weren’t even imagined when they were collected!

During the World Malacological Congress in Perth in 2004, Peter Beninger accessed a specimen of the scallop Hemipecten forbesianus to confirm that it had homorhabdic gills (all gill filaments are tubular structures called ordinary filaments). Instead, he found heterohabdic gills (gill filaments alternate between ordinary and larger U-shaped principal filaments). The result was that he was able to establish that gill type can be used as a soft-tissue taxonomic character of the Pectinidae. Prior to this, only Hemipecten stood in the way! This is a great example of how permanent collections help malacologists continue to test hypotheses and understand molluscan biology and taxonomy. ~ P.G. Beninger and Rachel Przeslawski

Week 23: INTERNATIONAL DAY FOR BIODIVERSITY

Who doesn’t love marvelling at the diversity of forms, colors, feeding modes and behavioural attributes of molluscs? The Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) is the international legal instrument for “the conservation of biological diversity, the sustainable use of its components and the fair and equitable sharing of the benefits arising out of the utilization of genetic resources” that has been ratified by 196 nations, including Australia. The theme this year is Biodiversity and Sustainable Tourism, chosen to raise awareness of the important contribution of sustainable tourism both to economic growth and to the conservation of biodiversity. Understanding our regional molluscan diversity and distribution, through ongoing work in taxonomy, ecology and evolution is critical to ensuring that we know what we have and where we have it- the fundamental first step in developing appropriate conservation measures. MSA is at the heart of this initiative in Australasia with members dedicated to the appreciation, study, and sustainable use of molluscs. Our societal code of ethics on conservation and endangered species is posted on our website and offers clear guidelines on appropriate collecting. ~ Lisa Kirkendale

Week 22: HOW DO MOLLUSCS BUILD THEIR SHELLS?

Anyone who has been for a stroll along the beach has most likely been struck by the natural beauty of sea shells. The shapes, patterns and colours of shells are ultimately controlled by macromolecules secreted by an underlying organ called the mantle. Bernie Degnan and colleagues at the University of Queensland are investigating which genes are involved in this process and whether they are conserved between molluscan species. Surprisingly, they have found very little similarity in the shell-building gene sets across the species investigated – instead, it appears that each species uses a different combination of ‘ancient’ genes (genes that originated even before the origin of molluscs), and genes that have evolved more recently. Although this makes it hard for researchers to piece together a general picture of how molluscs build their shells, it is most likely one of the reasons for the beautiful diversity of shells produced by these animals. ~ Carmel McDougall

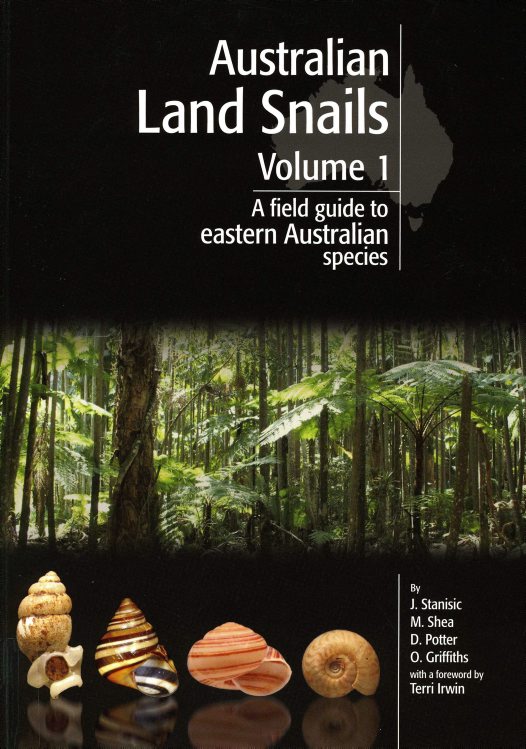

Week 21: AUSTRALIAN LAND SNAILS, VOL 1

In 2010, a group of Australian malacologists published the first book in over 140 years to document native Australian snails. Featuring almost 600 pages of colour images, descriptions, distribution maps, and notes on habitat and ecology, the book includes 794 species in 44 families along the eastern coast of Australia, including over 300 species described for the first time. Australian Land Snails Volume 1 is the most comprehensive guide to our amazing diversity of land snails and has become a valuable resource to professional malacologists and amateur naturalists and everyone in between. ~ Rachel Przeslawski

Week 20: OUTBREAK AND ERADICATION OF MYSTILOPSIS SALLEI

How can such a little creature cause so much drama! In March 1999, aggregations of a small mussel were found throughout the Cullen Bay Marina in Darwin. These mussels were identified as Mytilopsis sallei, a highly invasive mollusc. Although they are little (maximum 2.5cm), they are reproductively mature within four weeks and are highly fecund. Many tons of sodium hypochlorite and copper sulphate, $2.2 million, and two months later, Cullen Bay Marina was declared free of M. sallei, becoming the world’s first example of the successful eradication of an established marine pest population.

An article describing the discovery of this pest was published in 2000 (Willan et al. 2000), and is currently the highest cited paper ever published in Molluscan Research. ~ Richard Willan and Carmel McDougall

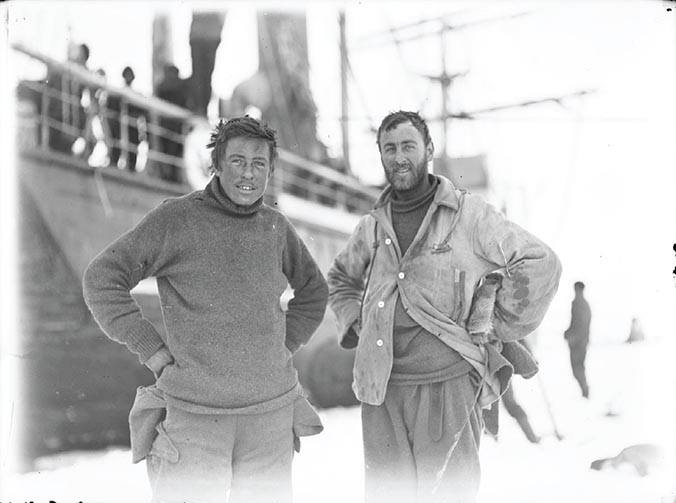

Week 19: CARL LASERON – VETERAN, EXPLORER, MALACOLOGIST

Charles (Carl) Francis Laseron was born in America in 1887, before migrating to Australia in 1891. Coming from a modest background he was unable to afford university fees, but obtained a diploma in geology from Sydney Technical College, later working as a lecturer and collector with wide interests including geology, palaeontology and eucalypts. In 1911, Laseron joined the Australian Antarctic Expedition under Sir Douglas Mawson, acting as a general scientific assistant and undertaking two major sledging journeys (below right, with Percy Correll). During WWI he enlisted in the Australian Imperial Forces, and was wounded in the leg by sniper fire on the second day of the Gallipoli landings. He recovered from the injury but was discharged.

After the war, Laseron managed the art collections at the Sydney Technical Museum until resigning due to a dispute with the museum curator. He then pursued a number of interests, including establishing an antiques business and acting as clerk for the Colonial Sugar Refinery Company. During this time his interest in natural history turned to molluscs. He published 6 works on Australian malacology (including revisions of NSW Leptonidae and Triphoridae), completed 20 essays, produced over 2000 drawings and described hundreds of new species. He became an honorary correspondent of the Australian Museum and a fellow of the Royal Zoological Society of New South Wales in 1952. ~ Carmel McDougall

Week 18: AN ONLINE GUIDE TO TASMANIAN MOLLUSCS

Molluscan taxonomy is in a continual state of flux, and our understanding of species occurrences grows daily. Because of this, regional field guides and species lists can rapidly become outdated. To address this problem, Dr Simon Grove, curator of molluscs at the Tasmanian Museum, used his extensive database of mollusc records around Tasmania to develop A Guide to the Seashells and Other Marine Molluscs of Tasmania in 2006.

With over 1750 species, this valuable online resource provides information on taxonomy and distribution, as well as spectacular specimen images, many of them taken by Port Arthur-based dredging enthusiast Rob de Little. As with many of its kin (e.g. Sea Slug Forum, Seashells of NSW), future support and maintenance is a concern because they are run by enthusiastic malacologists in their spare time. Any offers of help with overhauling the web-site onto a more modern, lower-maintenance platform will be gratefully received by emailing Simon at simon.grove @ tmag.tas.gov.au. ~ Rachel Przeslawski

Week 17: OCTOPUS GENETICS AND THE IMPACTS OF CLIMATE CHANGE

What impact will climate change have on our oceans and biodiversity? This is a massive question, however some clues can be found by studying what has happened in the past. The study of deep-sea and Antarctic octopods by Jan Strugnell and colleagues has provided valuable insights into historic speciation events associated with major environmental changes. Genetic analyses indicate that deep-sea octopods diverged from other southern-ocean species at a time of significant climactic change in the region. The climactic changes likely initiated new currents that helped Southern ocean species to move into the deep-sea. Octopus genetic signatures are also consistent with a more recent collapse of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet in the Pleistocene, which likely enabled dispersal through the resulting trans-Antarctic seaway. It is expected that other animals were similarly impacted by changing currents and passages. These studies show that major environmental change can have major impacts on species and biodiversity. ~ Jan Strugnell and Carmel McDougall

Week 16: GIANT CLAMS, SUNLIGHT, AND OCEAN ACIDIFICATION